Christine Lagarde was invited to the Federal Reserve's annual conference in Jackson Hole presumably to be terrorized by Jerome Powell.

The Federal Reserve chairman opened the conference with a speech in which he stressed, right from the start, that the task of the US central bank is to bring inflation up to the 2% target, because "inflation is still too high". The ECB must do the same, regardless of the growing pressure from the bankrupt governments in the eurozone.

Powell also responded in this way to a growing number of calls, including from Paul Krugman, for raising the inflation target to at least 3%. The justification offered by these so-called economists, for whom the exponential function seems to be a total enigma, is that expected inflation can be higher and not adversely affect consumers.

Such an argument is very hard to fight, because it implies a hard fight against stupidity or abjection or a combination of both. As they say, it is not good to get into an argument with a fool, because it brings you down to his level and defeats you by experience. The difficulty is magnified even more if it is not stupidity, but only abjection.

Any self-respecting economist, even if they have only taken elementary courses in statistics and econometrics, knows that all variables used in analysis and forecasting models must be stationary, i.e. characterized by constant means, variances and covariances over time.

Any "economist" who claims that all the world's problems would be solved and monetary policy would become effective if the inflation target rises from 2% to 3% or 4% is nothing more than a "useful idiot" hoping to grab more delicious crumbs from the masters' table.

"We stand ready to raise rates further, if necessary, and we intend to keep monetary policy tight until we are confident that inflation is moving sustainably toward our objective," the Federal Reserve chairman stressed in the very opening of his speech, and then did not forget to blame Russia for the acceleration in global inflation.

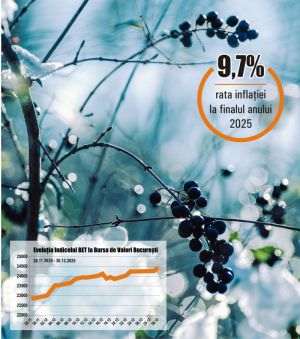

Jerome Powell ignored the fact that Russia's influence on inflation in the United States is non-existent in a broader historical context. Official data and estimates from the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis show a period of remarkable price stability prior to the establishment of the Federal Reserve in late 1913, significant growth in the postwar period, and an unprecedented boom since the early 1970s (see chart).

How has unprecedented economic growth been possible in a century marked by significant deflationary periods? And how does the Federal Reserve explain the exponential rise in inflation that began more than half a century ago?

In his speech, the Federal Reserve Chairman acknowledged that "tighter overall financial conditions typically contribute to slower growth in economic activity, and there is evidence of that in this cycle as well," as "industrial production growth has slowed and the amount spent on residential investment has declined in each of the last five quarters."

However, "our inflation target is and will remain two percent," Powell added, and then stressed that while "the current stance of policy is restrictive, putting downward pressure on economic activity, employment and inflation," the US central bank "cannot identify with certainty the neutral interest rate, and therefore there is always uncertainty about the exact degree of monetary policy tightening."

If this is happening at the level of the most powerful central bank in the world, what does the disaster look like at the level of other central banks, especially those that religiously await external indications, such as the National Bank of Romania?

Is Jerome Powell's statement an admission that economic science and its modern perceptions, which should make it possible to plan market economies so that the growth of prosperity cannot be stopped, are nothing?

But then how do the "readers" of sophisticated models justify their existence, models that are the pride of central bankers, especially when they use them to disclaim any hint of responsibility because "the models have shown that we should do so"?

Jerome Powell ended his speech at Jackson Hole with a statement that was astonishing and deeply damaging to the confidence of citizens in the competence displayed by central banks.

"As is often the case, we are navigating by the stars under cloudy skies," the Federal Reserve chairman said, and then stressed that "we will proceed carefully as we decide whether to tighten further or, on the contrary, hold the policy rate steady and wait for additional data."

"We'll keep going until we get the job done," concluded Jerome Powell, again paraphrasing the title of the autobiography of Paul Volcker, the legendary Federal Reserve chairman of the 1980s, who took the policy rate to 20% in the fight against inflation.

As the theme of this year's symposium was "Structural Changes in the Global Economy", Charles Jones, a professor at Stanford Graduate School of Business, presented an analysis entitled "Prospects for Long-Term Economic Growth".

It says that "ideas are harder and harder to find" amid "stabilising education levels", and "we have to run faster and faster just to stand still", a position it equates with average multi-year economic growth of around 2%.

The Stanford professor also fails to explain the implications of a 2% increase, which leads to a doubling of the economy in about 35 years, for energy consumption.

What about the fight against anthropogenic climate change? And then why is growth at any cost necessary when development is far more important?

Another leading US professor, Barry Eichengreen of the University of California, Berkeley, has argued that we must continue to live with high levels of public debt because there are no practical ways to reduce it.

Unfortunately, Professor Eichengreen did not come up with convincing arguments about the sustainability of such a "scheme", especially since the public debt accumulated in recent years has not had a positive effect on economic growth. Avoiding collapse and prolonging the agony is not a sufficient argument, as future interventions will have to be made at ever shorter intervals and at ever higher amounts, until the threshold of helplessness is reached.

Even studies from the IMF show that the marginal efficiency of public debt in developed economies has become subunitary, i.e. adding one dollar to public debt produces less than one dollar. How can such a situation be sustainable in the long term, especially when more and more voices argue that the era of low interest rates was just a historical aberration, and that the new normal would now be characterised by benchmark interest rates around the 5% threshold?

ECB President Christine Lagarde's speech concluded the first day of the Jackson Hole Symposium, and was notable in particular for avoiding any statements that could provide interpretations of the forthcoming monetary policy decisions. That is all the European Central Bank can do.

America is still hopeful that a change can take place in the White House next year. In the European Union there is no such hope, because the political and bureaucratic framework has been built precisely to prevent change, especially change that threatens centralised rule.

It is precisely for this reason that the only way out of the darkness maintained by the kakisto-idiocracy based in Brussels and in the other capitals of the European Union can not be found without a historical collapse.